Projects of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar are funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Free State of Thuringia, represented by the State Chancellery of Thuringia, Department of Culture and the Arts.

History

The Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek through the centuries

1547 · The battle at Mühlberg and the beginnings of the Ducal Library

The history of the Weimar library started with the battle at Mühlberg on 24 April 1547 during which the army of Emperor Charles V defeated the Protestant troops under the command of the Saxon Prince Elector Frederick the Magnanimous (1503-1554). After this crushing defeat, the Prince Elector established his new residential seat in Weimar and had his valuable library in Wittenberg tranferred to Weimar that same year. Most of the collection ended up in Jena where it comprised the core holdings of the newly established library there. A smaller part consisting of some 500 volumes remained in Weimar. This marked the beginning of the ducal book collection.

1691 · The systematic expansion of the library begins

New territorial divisions in the 16th and 17th century enriched the collection, but also fractured and dispersed it. A period of sustained expansion finally began in 1691. An inheritance contract between the Duchies of Saxony-Weimar and Saxony-Eisenach on 12 July 1691 entailed ownership of five hundred volumes previously owned by then defunct dynastic branch of Saxony-Jena to the Weimar court. This windfall provided Duke Wilhelm Ernst of Saxony-Weimar (1662–1728) an occasion to expand his library. The collection would play an integral part in his plans to make the residential seat of Weimar a cultural centre.

1723 · The library holdings grow to 20,000 volumes

At the start of the 18th century, the library was extensively expanded with the purchase of private collections and soon gained a reputation for its high scientific value. Books were acquired from the private collections of the Weimar chancellor Moritz von Lilienheim, Baron Balthasar Friedrich von Logau in Breslau, the Danish scholar Marquard Gude and the famous Wittenberg universal scholar Conrad Samuel Schurzfleisch, who had served as director of the Weimar library since 1706. In just 34 years, the library’s holdings increased from 1,500 volumes in 1691 to approximately 20,000 in 1723. However, there was still no uniform classification system, and the rooms where the books were stored in the Residence Castle were hardly representative of a library of such status.

1750 · Bartholomaei is appointed head librarian; a new era begins

A new era for the library began in the middle of the 18th century. The theologian Johann Christian Bartholomaei was appointed head librarian. Thanks to the sale of duplicates, he was able to consolidate the operations of the library for the first time. He also produced a catalogue of works totalling 60 folio volumes. With the generous support of Duke Ernst August II Constantin (1737–1758), the library disposed of an annual budget for purchasing new works.

1766 · The turning point: Duchess Anna Amalia decides to move the collection to the Rococo Hall in the Green Castle

After the death of her husband Duke Ernst August II Constantin, Duchess Anna Amalia (1739–1807) assumed responsibility for the duchy until her son came of age in 1775. It was she who decided to move the book collection out of the Residence Castle. The State Master Architect August Friedrich Straßburger designed a late Rococo-style library hall inside the so-called “Green Castle” which was built between 1563 and 1565. In 1766 the library was transferred into the newly installed Rococo Hall. From this point on, the library with its almost 30,000 volumes attracted renewed public attention.

1797 · Duke Carl August appoints Goethe and Voigt as superintendents and Vulpius as librarian

In 1797 Duke Carl August appointed Privy Counsellors Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Christian Gottlob Voigt to manage the library as its superintendents. Both were devoted to expanding the library and ensuring its holdings and usability could meet the new and increasing demands. Only two months after their appointment, they issued new library regulations which explicitly laid out the terms for when and how long books could be borrowed. Between 1797 and 1801, a total of 475 persons were registered users of the library, equivalent to 6.33 % of Weimar’s population at the time.

Under Goethe’s and Voigt’s direction, the library became a more bureaucratically organised, systematically run institution, the independence of which the Duke duly acknowledged. By 1832, the year Goethe died, the collection had grown to 80,000 volumes. It was mainly Christian August Vulpius, Goethe’s brother-in-law, who ensured that all the new books were catalogued and properly shelved for usage. Vulpius was employed at the Weimar library from 1797 to1826.

1805 · The Goethe annex: The expansion of the Green Castle

Upon Goethe’s urging, the library was expanded between 1803 and 1805 with an annex built on the south-facing side of the Green Castle. There was simply not enough space in the Rococo Hall anymore for the library’s growing collection of books and artworks. Goethe supervised the construction and often became involved in design decisions. Alongside copies of famous paintings by Carracci und Franceschini, Goethe had plaster casts of ancient portrait busts and sculptures installed along the staircase.

1825 · The city wall turret is converted into a “Book Tower”

Duke Carl August commissioned C.F.W. Steiner to convert and expand the turret of the former city wall (built in 1453) into storage space for his military library from 1823 to 1825. One could reach the upper level via a wooden spiral staircase dating from 1671 which was originally installed in Weida Castle. The shaft of the staircase was crafted from a single oak trunk measuring 12 metres in length, for which the tower had to be raised with a 12-window roof lantern. In addition to his military library totalling 5,000 volumes, Carl August also kept his coin, medallion and globe collections in the tower. In 1831 a three-volume list of the works in the “Book Tower” was published, edited by Friedrich Theodor Kräuter. Catalogue entry. Available as a free download here.

1849 · The Coudray annex: The beginning of musealisation

In the years after the death of Duke Carl August and Goethe, the library gradually became a pantheon of Weimar Classicism. The old ducal portraits displayed in the second gallery were joined by the greats of the Classical period: busts and paintings of Weimar’s famous poets and philosophers. Johann Joseph Schmeller’s painting “Johann Wolfgang Goethe in his workroom, dictating to the writer John”, of 1834 was gifted to the library and soon became a devotional image of the Goethe cult. More and more people expressed interest in visiting the library. Eventually it began charging visitors 50 pfennigs for admission to the Rococo Hall.

The memorial culture reached its first zenith with commemoration of Goethe’s 100th anniversary in 1849. The commemorative festivities served as an occasion to celebrate the grand opening of the north annex, designed by architect Clemens Wenzeslaus Coudray and built between 1844 and 1849. This final building project gave the library its present-day dimensions. The administrative offices were installed in the new extension, while the Goethe annex was used as storage space for the book stacks. By 1875 the total holdings comprised some 170,000 volumes.

„Of all the monuments of Weimarian spirit, the library made the greatest impression on me.“

Adolf Stahr, 1852

1919 · The Grand Ducal Library becomes the Thuringian State Library

Following the abdication of the Grand Duke on 9 November 1918, the Grand Ducal Library was renamed the “Weimar Library” in December 1918, and then was renamed again in August 1919 as the “Thuringian State Library”. Instead of benefiting the court alone, the library adopted a new mission to provide academic literature to a broad segment of the population in service of public education. However, the library neither possessed the holdings nor appropriate premises to meet this challenge. By 1919 the main library building was crammed from the basement to the attic with almost 400,000 volumes. The haphazardly produced catalogues could only be deciphered with the help of the librarians, and the budget for acquisitions equalled that of a small community library. Against this background, the library cultivated its image as a museum and memorial site of the Classical era.

1933 · National Socialism and political alignment

After the National Socialists seized power in 1933, the Thuringian State Library – as was the case with all public institutions in Germany – underwent political “alignment” at various levels. It accepted the literary estates of Nazi-confiscated libraries of local branches of the Social Democratic Party, workers’ libraries and private libraries of Jewish families. These holdings are designated today as Nazi-confiscated cultural assets. A team of provenance researchers is currently investigating all items which the library acquired between 1933 and 1945. A number of items have meanwhile been returned to their rightful heirs. For more on this, read about the provenance research activities at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

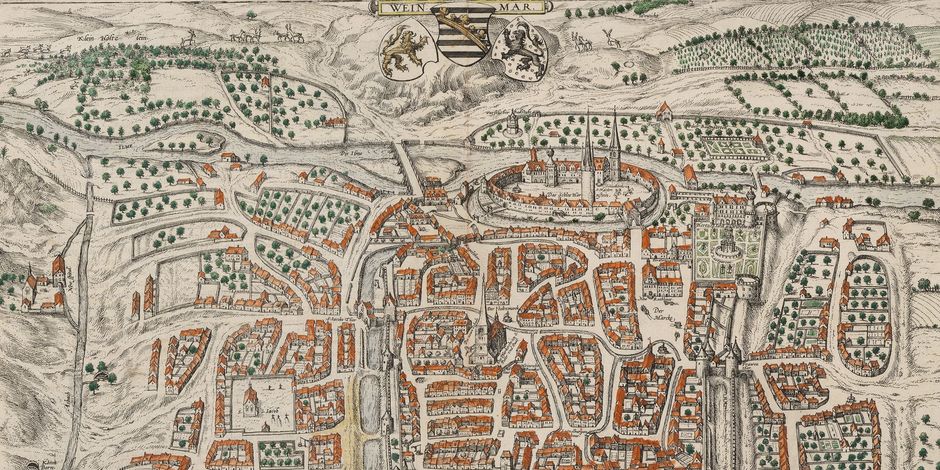

During the National Socialist era, the library was one of the public administrative buildings in the centre of the city of Weimar. The so-called Fürstenhaus, today's Hochschule für Musik, was the seat of the Reich Governor of the NSDAP Gauleitung of Thuringia and the Thuringian Ministry of Education. To the north of the library, in the stables behind the Residenzschloss, was the Gestapo headquarters from 1936 to 1945. To the south-west of the library, at Marienstraße 13/15, the Thuringian State Office for Racial Affairs had moved into some buildings. The library performed a service function for this and other National Socialist administrative organisations. A city map of Weimar from 1938 shows the distribution of ministries in the city.

1937 · Opening of the reading room

The space had long been recognised as inadequate for the library's users. In 1934, the decision was made to convert the former archive room on the ground floor of the library into a modern reading room. The reading room was furnished between 1936 and 1937 and opened on 6 March 1937. The windows overlooking the city had already been enlarged in 1934. In addition, a ceiling light was installed, each table was given its own lamp and a reference library was set up on the wall shelves. The reading room now had room for 24 people. At the same time, two rooms on the ground floor (Coudray extension) were converted into a book issue and catalogue room in 1936.

The modernisation of the library between 1934 and 1937 also included the repair of the north and west façades, a repainting of the Coudray staircase, the installation of additional fire doors, central heating and new toilets.

1945 · Reestablishment of the library and ideological cleansing

During World War II, the majority of the library’s holdings were removed and stored for safe-keeping at various depots in the area. Most of the books found their way back to the library after 1945 without any significant losses, and the systematic removal of all writings of National Socialist ideology began. Almost 10,000 volumes were “purged” during this phase of ideological “cleansing” from 1945 to 1951.

1951 · Expansion as a general academic library

In 1951 the library assumed the tasks of a central academic regional library. Together with the branch library in Jena, it was responsible for supplying the region with academic literature and coordinating the lending activities. The goal was to create a general academic library which would contribute to advancing the socialistic project. It was supposed to assume public educational tasks but possessed neither the necessary financing nor staff to do this, and its traditional holdings were poorly equipped to achieve this objective. The students at the technical colleges and universities in Weimar comprised the new target group. The literature of Weimar Classicism, the focus of the collection activities until then, fell to the wayside. Instead the newly established Central Library of German Classicism within the National Research and Memorial Sites of Classic German Literature in Weimar (NFG) assumed the responsibilities of a specialist library of literary studies in 1954.

1953 · The library receives deposit copies from Thuringian publishers

As of 1953 the library was the only central state repository to receive deposit copies of all works (except newspapers) from Thuringian publishers situated in the districts of Erfurt, Gera and Suhl. This responsibility was reassigned to the University Library in Jena in 1983. The permanent storage of these deposit copies is and will remain one of Herzogin Anna Amalias Bibliothek’s central responsibilities in years to come. With funding from a special programme of the Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media (BKM), the library transferred a total of 1,300 deposit copies into age-resistant cases in 2019 to prevent further damage and ensure their long-term preservation. For more information, read about the protective packaging of deposit copies of Thuringian publishers.

1969 · The Thuringian State Library becomes the Central Library of German Classicism

In 1969 the Thuringian State Library was integrated into the National Research and Memorial Sites and was merged with the smaller library at the institute. It also adopted its name, the Central Library of German Classicism. Its holdings were thus expanded by the library of the Goethe Society, Schiller’s and Nietzsche’s private libraries, and the Faust collection of Gerhard Stumme. From this time forward, the library focused its activities on German literature of 1750 to 1850 and gradually scaled back its operations as a regional library. Parts of the collection which did not correspond to the new guidelines (at least 20,000 volumes) were either sold to the central antiquarian bookshop in Leipzig or redistributed to other institutions. In 1969 the library possessed a total of approximately 750,000 volumes.

1991 · After reunification, a new name: The Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek

On 18 September 1991 after the peaceful revolution and German reunification, the library officially assumed a new task and a new name: the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Its main purpose was to serve as a research library of literary and cultural history with a special focus on German literature from the pre-Enlightenment to the late Romantic period.

1998 · The Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site

In 1998 the historic building of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek along with other Weimar sites of German Classicism were designated a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO. As justification for the distinction, it recognised the “Classical Weimar” ensemble as testimony to the enlightened, courtly but also civic culture of the period around 1800. More information: Classical Weimar – UNESCO World Heritage Site

2004 · Fire destroys the library

On 2 September 2004 a massive fire destroyed and damaged extensive parts of the collection and the historic library building. Experts have since determined that the cause of the fire was old, faulty wiring which had remained in constant use prior to the planned renovation of the building. The library had struggled under chronic under-financing in the years leading up to the devastating event. The use and upkeep of the building could no longer meet the necessary conditions for preserving and presenting the collections inside. More information: After the fire

2005 · The new Study Centre is opened

By 1998 the library holdings had grown to around 910,000 volumes. The search for additional storage space had become all the more urgent. Several external repositories were established, and in 2000, new construction and renovation measures commenced. The decision was made to expand storage capacity by using an existing historical building ensemble, the so-called Red and Yellow Castle directly opposite of the Historic Library. The construction work began in 2002 under the supervision of the architects Hilde Barz-Malfatti and Karl-Heinz Schmitz. The Study Centre officially opened in 2005. Around 170,000 volumes of academic literature categorised by subject area were now presented and directly accessible to library users from reference shelves.

2007 · Reopening of the Historic Library after the fire

On 24 October 2007, the anniversary of Duchess Anna Amalia, the Historic Library reopened after years of extensive renovation. Today the building houses the book restoration and conservation workshop, the special collections department and the head office. Some 40,000 volumes were restored and are now presented on the main level and first gallery of the Rococo Hall. The composition and arrangement of the books closely mirrors what one would have found in the mid-19th century. In keeping with the old principles of library organisation, the books are grouped by subject area without finer differentiation, e.g. history, theology, law, mathematics, philosophy, poetry. Many of the volumes on display were personally borrowed from the library by Goethe and other Weimar authors. One could argue that the books in the Rococo Hall represent the intellectual reservoir from which the Weimar writers around 1800 drew inspiration for their own works.

2018 · Agenda 2020

The Foundation Board of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar has approved the Agenda 2020 of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek which defines the fields of development for the archival and research library in the coming years: the Weimar lab for collection preservation, perspectives on collection expansion, activation and design of public spaces and collection rooms, digital library, and collection mediation and research.

More information (in German): Library director Reinhard Laube on the Agenda 2020

One of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek’s central tasks outlined in the Agenda 2020 is to create public areas and collection rooms to facilitate better access to the collections. An extensive discussion of the first artistic intervention in this context is provided in the 2020 publication:

Laube, Reinhard (ed.): Brandbücher | Aschebücher. Perspektiven auf Hannes Möllers künstlerische Intervention in der Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Mit Grußworten von Benjamin-Immanuel Hoff und Annette Seemann. Weimar: Klassik Stiftung Weimar, 2020. For free download, click here (in German).

2023 · Future Memory

The library's new strategic direction for the next four years is entitled „Future Memory - Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek“, building on the results of Agenda 2020.

The focus is on the three project lines »Discovering collections«, »Preserving originals« and »Contemporary witnesses reporting«. The focal points include the further development of the library's discovery system, the cataloguing and digitisation of the Weimar Military Library and atlas collection and the establishment of the workshop for the restoration of fire-damaged documents in Weimar-Legefeld as a core facility (specialist institute) for paper restoration, which acts in an advisory capacity and as a service point in conjunction with other specialist institutes. Another focus is also on the „Contemporary Witnesses Report“ project. To mark the 20th anniversary of the library fire on 2 September 2024, memories of the fire are being collected, together with ideas and wishes for the future of the library.

Further reading

Grunwald, Walther; Knoche, Michael; Seemann, Hellmut (Hgg.): Die Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Nach dem Brand in neuem Glanz. Mit Fotogr. von Manfred Hamm. Berlin: Meissner, 2007. Catalogue entry.

Knoche, Michael (Hg.): Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Kulturgeschichte einer Sammlung. [Weimar]: Klassik Stiftung Weimar, 2013. Nach einer 1. Aufl. bei Hanser, 1999. Catalogue entry.

Knoche, Michael (Hg.): Die Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar. Das Studienzentrum. Mit Fotografien von Klaus Bach und Ulrich Schwarz. Berlin: Nicolai, 2006. Catalogue entry.

Knoche, Michael: Die Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Ein Portrait. 2. erw. u. überarb. Aufl. Berlin: Otto Meissners Verlag, 2016. Catalogue entry.

Laube, Reinhard (Hg.): Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Erschienen in der Reihe "Im Fokus", hrsg. v. d. Klassik Stiftung Weimar. Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, [2022]. Catalogue entry.

Weber, Jürgen; Hähner, Ulrike (Hgg.): Restaurieren nach dem Brand. Die Rettung der Bücher der Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. Petersberg: Imhof, 2014. Catalogue entry.

Weimar 1: Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek [Bestandsgeschichte, Bestandsbeschreibung, Kataloge, Quellen und Darstellungen zur Geschichte der Bibliothek, Veröffentlichungen zu den Beständen]. In: Handbuch der historischen Buchbestände in Deutschland, hrsg. v. Bernhard Fabian, hier Bd. 21: Thüringen: S-Z, hrsg. v. Friedhilde Krause u. bearb. v. Felicitas Marwinski. Hildesheim u.a.: Olms-Weidmann, 1999, S. 101-127. Catalogue entry. Available as free download here.

You can find additional sources for further reading in the Bibliography on the History of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek and Its Collections.