A – F

A as in Aphorism

Nietzsche liked using this stylistic device to formulate his ideas tersely and pithily. He consciously presented his ideas as aphorisms because it allowed him to explore various aspects instead of establishing a rigid and dogmatic philosophical system.

B as in Bee

Nietzsche described enlightened minds as “intellectual honey-gatherers”.

C as in Chaos

Nietzsche claims that the world is not well-structured but is rather shaped by coincidences – a place where contradictory forces wrestle for domination, where structures rise and then decay. This is what engenders newness: “One must bear chaos in oneself in order to give birth to a dancing star.”

C as in Contradiction

Legend has it that Nietzsche’s texts contradict themselves; for every philosophical premise, one can always find the exact opposite. The truth is that Nietzsche wanted to understand life from many different perspectives. Obviously, this is reflected in his writings and philosophical musings. Not only does he speak with the authority of an author, he also allows many others to voice their opinions. Often these are merely slight shifts in meaning, the various facets hidden within an idea and in various contexts. Pay close attention when reading!

D as in Definition

Everything has a history – even words. Language changes over time. According to Nietzsche, a single word can possess its entire etymology, and with every definition, a bit of its history is lost. Defining a term means assigning it an unalterable meaning. Therefore, Nietzsche claims “only that which has no history can be defined”. A word’s context, on the other hand, is more important than definitions. This explains why Nietzsche’s words sparkle and can take on very different meanings.

E as in Ear

“If one fails to understand, then one has no ear for it.” And Zarathustra declares, “They understand me not; I am not the mouth for these ears.” Human understanding does not always happen in the same way. Rather, everyone has their own ear, their own ability to listen and comprehend. Misunderstanding is far more likely to occur. Nietzsche – a philosopher of the physical body – not only raised philosophical attention to the ear, but also the stomach, digestion and the foot.

E as in Elisabeth

Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth was two years his junior. At the age of 39, she married the self-proclaimed anti-Semite Bernhard Förster, with whom she moved to Paraguay to live in a German colony. After her husband’s suicide and the financial ruin of the colony, she moved back to Germany. She dedicated herself to caring for her ailing brother and enthusiastically assumed curatorship of his intellectual legacy. She was known for being self-righteous and did not shrink away from intrigues and lawsuits. Despite having no secondary or university education, she overcame numerous obstacles and even won the respect of higher social circles, artists and intellectuals. Her management of Nietzsche’s estate was disastrous due to her numerous forgeries.

E as in European

Nations were narrow-minded and one-sided in Nietzsche’s view, and that is why he advocated for Europe. In addition to disparaging the short-sighted policies of nationalism, he invented the “good European” – a character that embodied the cultural, literary and musical values of Europe.

F as in Forms

Nietzsche not only wrote philosophical treatises, but also songs, dialogues, sentences, aphorisms, poems and parables. This anarchical diversity of forms corresponds to his distrust of the dogmatic nature of a single systematic perspective.

H as in Homeless

After quitting his position at the University of Basel, Nietzsche was homeless. Often afflicted by terrible migraines, he was in constant search for places where he could benefit from their climatic conditions and air pressure. He finally found optimal conditions in Sils-Maria, and in the winter, he moved to the warmer climes of Italy.

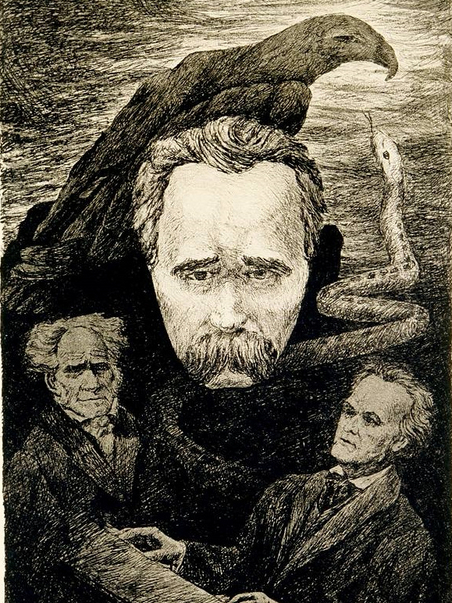

I as in Illness

How ill was Nietzsche? Did he go mad? Did he perhaps have syphilis? Those who are intrigued by such questions should first read a text by Nietzsche and then judge for themselves. Afterwards, if these are still the most important questions on their mind, maybe they should leave the reading to others.

J as in Judge for Yourself

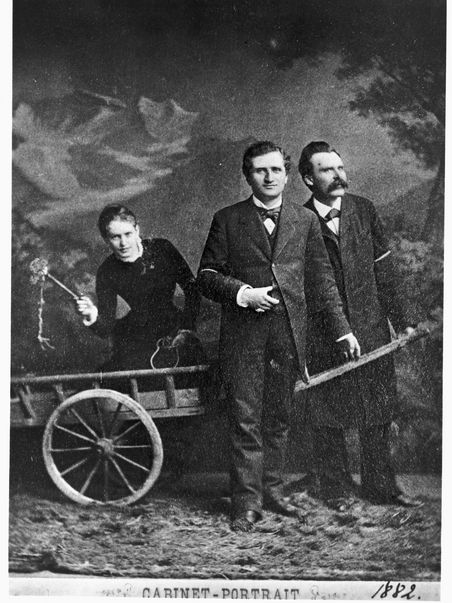

One can find ellipses and dashes throughout Nietzsche’s texts. He also often uses direct forms of address (we, you), poses rhetorical questions, suddenly interrupts a line of thought... Sometimes he presents a topic so polemically that it is impossible to remain neutral ... he practically demands that we take a moral position. With these and other tricks, Nietzsche wanted to encourage his readers to judge for themselves, not to remain passive, but to take his ideas a step further – – – . In 1882 Nietzsche wrote ten “Rules for Writing with Style” for Lou von Salomé, in which he urged to “leave it to one’s reader alone to pronounce the ultimate quintessence of our wisdom.”

M – S

M as in Music

“Life without music would be a mistake,” Nietzsche declared. He himself could play the piano very well, improvised with passion and even composed his own music.

N as in Nietzsche

Nietzsche was born in 1844 and died in 1900. To this day, he remains extremely popular as a philosophical phenomenon, and his ideas continue to influence many people. One can divide is working life into ten-year intervals. In 1869 he began working as a professor of classical philology (ancient Greek and Latin) in Basel, Switzerland. In 1879 he quit his job and started leading an itinerant life as a philosopher with no place of residence. He wrote his most influential philosophical works during the following ten years. In 1889 he suffered a mental breakdown in Torino and was cared for by his mother and sister until his death.

R as in Röcken

This is where Nietzsche was born on 15 October 1844. His father was a Protestant minister in a small village church. Today one can visit Nietzsche’s grave there, as well as a small but fascinating Nietzsche museum.

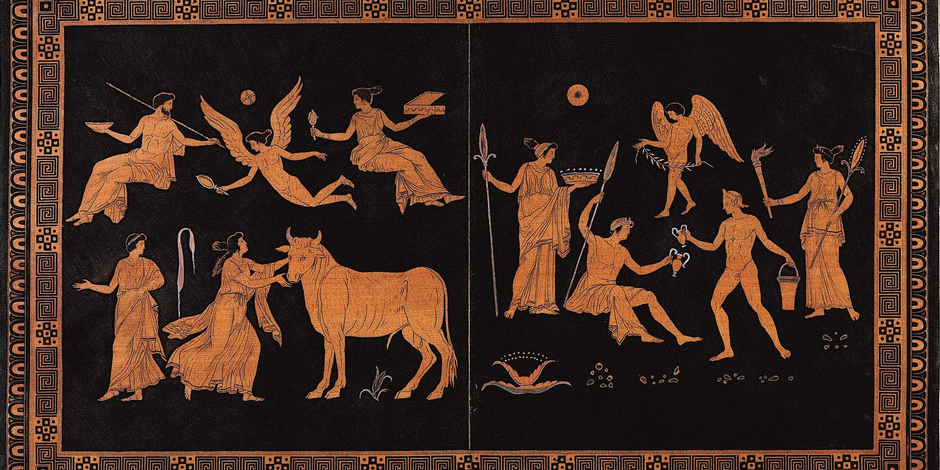

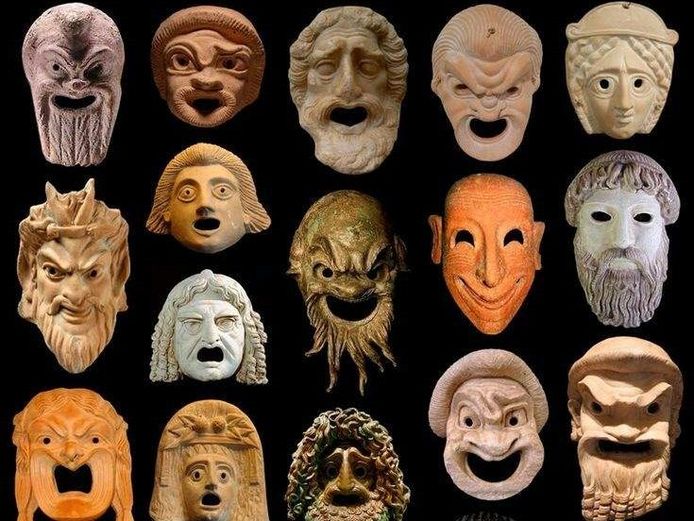

S as in Symbolic Figures

For Nietzsche, the “what” (the content) was not the only relevant part of a statement, but also the “how”, i.e. how it was presented, and “who” said it. Sometimes only a wanderer could deliver an insight, and occasionally a fool came up with a pearl of wisdom.

That is why one finds numerous symbolic figures in Nietzsche’s works, such as the wanderer, the free spirit, the hermit, the sage and the Antichrist. In this way, Nietzsche tied statements and positions to certain figures, to their experiences, biography and corporeality.

W as in “Will to Power”

Probably the only book in the history of philosophy which never existed. Although he jotted various drafts in his notebooks (along with ideas for numerous other books), Nietzsche eventually scrapped his plans in 1888. The so-called “magnum opus” entitled “The Will to Power” is actually a compilation of posthumous texts and forged passages penned by his sister Elisabeth.

W as in Whip

Often quoted – often misunderstood. In Nietzsche’s philosophical narrative Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Zarathustra meets an old woman who gives him rather dubious advice: “Thou goest to women? Do not forget thy whip!” Here is a woman speaking about all women as if they dominated through threats and violence. Thus, women are shown to be the harshest judges of other women! In a famous photo arranged by Nietzsche himself, we see him standing next to his friend Paul Rée in front of a wagon in which Lou Salomé is sitting – and who is brandishing a little whip. One could also interpret this sentence to mean “Don’t forget that she also has a whip!” …

Y as in “Yes-sayer”

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, the term “amor fati” (literally “love of fate”) stands for the affirmation of life especially when it is difficult and painful. Suffering and setbacks are not arguments against life but are necessary for one’s transformation into love.

![Zarathustra [Translate to English:] Superhero figure](/assets/media/a/5/csm_Melusine_Brant_Zarathustra_73aae39ce7.jpg)