Is open today

General opening hours

Tue–Sun (closed Mon)

9.30–18:00

Discover Cranach in the Renaissance Hall of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek. The exhibition includes works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, the Younger, and their shared workshop, which was one of the most prolific in art history. It produced thousands of artworks – more than any previous artist. There was no medium that Cranach had not mastered, and each is represented in the exhibition – paintings, graphic works, illustrated books and medals. For Cranach’s contemporaries, these works produced an overwhelming and unprecedented torrent of images. Today, Cranach’s legacy fascinates us more than ever and forges a connection to those who lived during the Reformation:

How was public opinion shaped by images? How were they used to present someone in a better light, or to ridicule one’s enemies? And how was it possible to produce and distribute so many pictures in such a short time?

Is open today

General opening hours

Tue–Sun (closed Mon)

9.30–18:00

Platz der Demokratie 1

99423 Weimar

Adults

6.00 €

Reduced

4.00 €

Pupils (16-20 years)

2.00 €

Combo ticket - Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek

12.00 €

The exhibition is staged in the Renaissance Hall which was built only a few years after Cranach’s death and offers a historically contemporary setting for the displayed objects. The hall is one of the oldest rooms in what was once known as the “Renaissance Castle” completed in 1569. As part of the ducal residence, the hall is closely tied to the Ernestine dynasty and the stately rooms of this period in the immediate vicinity, such as the Weimar City Church of St. Peter and Paul with its impressive retable by Lucas Cranach the Younger, and the City Castle.

The Renaissance Hall is part of the topography of the ducal residence which visitors in Weimar can still experience today. Although Cranach’s paintings have been displayed in the castle in recent years, some of them have always hung in the library. In this respect, the library is home turf for Cranach in Weimar.

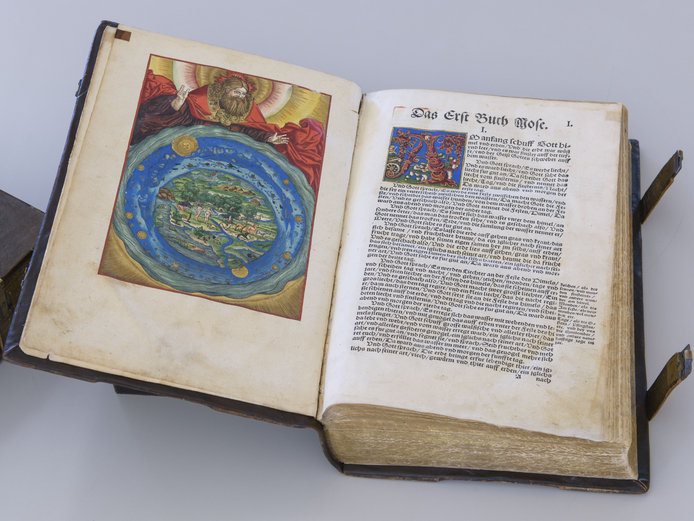

Five hundred years ago, a central question on everyone’s mind was: What must I do to save my soul? For life on earth was short, and the fate of the soul, eternal. Martin Luther questioned the conventional answers and sharply criticised the Roman Catholic Church in public. In this conflict, images were a welcomed means for advocating one’s position, and Lucas Cranach the Elder was one of the first to take sides. He and his workshop portrayed Luther as a hero and depicted his adversaries with mockery. Most significantly, they illustrated Luther’s translation of the Bible, of which the first complete edition was published in 1534.

One of the highlights of the exhibition, therefore, is the Weimar Luther Bible, one of the rarest and most lavishly illustrated copies that exist today. Nonetheless, Cranach had no qualms with producing works of art for Luther’s enemies – no distinguished artist would turn down an interesting commission, and Cranach was so good that everyone wanted to have his pictures.

The secret to Cranach’s success had as much to do with efficiency as it did flexibility. He had set up his workshop in such a way that numerous artists could quickly produce pictures which uniformly adhered to the “Cranach style”. Much like the “copy and paste” method graphic designers use today, Cranach often reused, cut out and applied certain motifs – tasks he could easily delegate to his employees. Cranach was flexible in the way he created pictures which possessed a certain ambiguity or expressed a different message by means of a few minor alterations. For example, a naked woman with children could represent a Christian virtue, or refer to ancient tropes, or simply express pure eroticism. This enabled him to appeal to new groups of clients or quickly react to newly trending themes.

Portrait painting was one of the main pillars of Cranach’s business. They were always popular and needed more than ever. Five hundred years ago, the times were as eventful as they are today, and similarly, the expectations and hopes of many were projected on certain individuals. Depending on the commission, the portraits were painted with great attention to detail – such as that Sybille von Kleve, the most stunning female portrait ever painted by Cranach – or small and schematically if numerous portraits were required. They always presented individuals in certain roles, the embodiment of a desired image: the beautiful woman who conducted herself modestly, or the erudite theologian whose expression exuded resolve, or the strong prince who saw himself as the guardian of truth and defender of his dynasty. Cranach’s strategy was so successful that we can hardly imagine the protagonists of the Reformation, like Martin Luther, Frederick the Wise or John Frederick I, the Magnanimous, in any other way than how Cranach portrayed them.